Chances are if you’re into the world of martial arts cinema, the name Chang Cheh may be familiar to you, or at the very least, his works will be.

Directing such classics as Shaolin Temple (1976) The Five Venoms (1978), Crippled Avengers (1978) and Five Element Ninjas (1982), Chang was a very prolific director, working primarily in the genre with over ninety film credits to his name.

Another classic that Chang brought to the big screen was 1967’s The One Armed Swordsman, a classy wuxia about a swordsman who loses his arm and must choose between his new life with his lover or going back to protect his martial arts school.

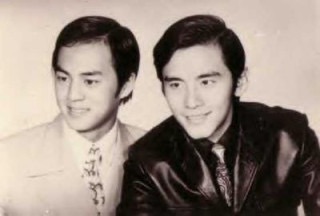

Starring Shaw Brothers legend Jimmy Wang Yu, The One Armed Swordsman quickly became one of Chang’s most iconic films and was quickly followed by a direct sequel, Return of the One Armed Swordsman (1969), a film that would feature minor roles for two actors who were about to become the stars of the next era of Chang’s career; those two being David Chiang and Ti Lung.

David Chiang was born in 1947 to famous Chinese actor parents and so became involved in the business from a young age, but when he was only twenty two years old, he was cast in Chang’s Dead End (1969) as a supporting role to Ti Lung’s lead but would soon become a star in his own right, often playing a mischievous, smiling scamp who would be typically killed off in graphic and dramatic fashion.

On the other side of the coin, Ti Lung, born 1946, had more of a martial arts background but still managed to become one of Shaw’s best leading men, starting with Dead End (1969) and starring in films throughout the seventies before even enjoying a career resurgence in 1986 with John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow. Ti’s roles were generally more varied but often, he was cast as the old school wuxia hero — even in A Better Tomorrow, he has a more jaded, serious edge to him, and in his outings with Chiang, their individual personalities often beautifully contrasted.

In the space of about eight years, Chang, Ti and Chiang — collectively dubbed the ‘Iron Triangle’, would make over twenty films together, in which Chiang and Ti would play allies, enemies, brothers and almost everything in between.

Which brings us back to The One Armed Swordsman — by the time a third film was to be made, star Jimmy Wang Yu had been ousted due to the star being difficult and had thus defected to the studio’s rivals, Golden Harvest so they decided to do what most films do nowadays and reboot.

This third film, fittingly dubbed The New One Armed Swordsman, would be one of six films released by Chang in 1971, all of which are Iron Triangle films (technically, King Eagle only features Chiang in a cameo), but in my opinion at least, this is not only his best to release that year, but arguably one of his finest overall (and my personal favourite).

The New One Armed Swordsman stars Chiang as Lei Li, an arrogant martial artist who becomes an introverted, disgraced shell of himself after losing a battle in which he cuts off his own right arm in penance.

Now working as a lowly bar servant, Lei Li attempts to keep to himself, retired from martial arts and allowing himself to get bullied by the bar patrons until one day, a warrior called Fung (portrayed by Ti at his most handsome) appears and the pair become fast friends.

Unfortunately, soon enough, tragedy strikes when Fung is murdered by the master who Lei lost to previously, forcing him to take up arms to avenge him.

The New One Armed Swordsman is a curiosity in the Iron Triangle series of films in that it almost switches the roles of Chiang and Ti — though Chiang begins the film in his typical rambunctious state, after he loses his arm, he becomes much more withdrawn, quiet and brooding.

Even the film’s de facto love interest, Ba Jiao (portrayed by the beautiful Ching Li), feels much more ancillary than the typical formula established — Chiang’s characters are typically womanisers, or at least romantic, but that isn’t the case here.

Despite Ba Jiao’s clear affections for him (that feel more born out of pity than anything), Lei Li never seems to show romantic interest in her, or for any woman in general.

Then there’s Ti Lung’s Hero Fung, who is introduced with a swelling musical sting (the score here borrows much from other films, mostly from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service), and Fung is much more the smiling, charming hero, and much like Chiang would do in other films, receives a gruesome death at the hands of villain Ku Feng.

Sure, Fung still is a character dreaming of escape and typical of Ti’s roles is the picturesque image of masculinity, all sharp features and broad shoulders, but once again, he seems to not take notice of Ba Jiao in a romantic manner and spends much of his screentime fascinated with Lei Li.

The New One Armed Swordsman is a much slower and sombre affair than one might expect; the middle stretch in particular is practically devoid of action but this does well to develop our characters, particularly Lei Li, showcasing the self-imposed misery and exile in which he wallows.

This changes only as Fung comes into the picture, where Lei Li finally seems to lighten up, with Ba Jiao even remarking “Lei Li, I’ve never seen you smile before!” in a scene where she looks on at the two men as they seem to find a shared connection.

Homoeroticism has often been a disputed factor of Chang Cheh’s works and indeed, action as a whole, with John Woo, Chang’s protégé, often having themes of male friendship in his works.

For Chang, however, works like The Duel (1971) and The Pirate (1973) provide great examples of such, with focus on brotherhood and an eroticism to the way they film Ti Lung’s body that isn’t unlike the way many other films would sexualise a woman. In The Duel, the camera glides across his body, his physique, capturing him like an Adonis.

Chiang, on the other hand, is seldom filmed in the same way; instead the eroticism is typically more entwined with the ways his characters suffer and die; geysers of blood, or even being pulled apart by horses. Outside of death sequences, Chiang is typically filmed more delicately, and perhaps arguably in a more ‘feminine’ way, at least for Chang, who prefers to film women in a more conservative manner.

If we take Ti’s body being filmed in such a way as an appreciation for him from a purely athletic perspective, then in the opposite way, the lithe, more fragile Chiang is admired in a way that is more adoring than objectifying, at least, when he isn’t dying to further Ti’s plot, in which his death serves as the objectification.

The New One Armed Swordsman marks one of the few times in which Ti dies for Chiang and not the other way around (one of the few other examples being the previous year’s Vengeance!) and in the film’s third act, Chiang must take up the more traditionally masculine role of the fighter again, even though it’s clear all he wanted was to live a life with Ti, something they had made plans for just a few scenes earlier — “I must avenge him.” he states as Ba Jiao attempts to comfort him; the camera zooms in on his face, and it’s as if he barely even notices she’s there.

What makes the film curious is that to call it simply ‘homoerotic’ would be to undersell it; just as the original The One Armed Swordsman was a love story, so is this sequel; it’s the tragic love story between two men.

As mentioned, these dynamics between men are heavily prevalent in Chang’s works, with queer undercurrents often being noted — take The Magnificent Ruffians (1979) in which the Venoms shoo off female attendants to share a communal bath together, or in The Duel, in which Chiang and Ti fight in the rain and mud, both eventually coming to a common understanding as they stare at each other, breathless and dripping wet. Some scholars even speculate the director himself may have been queer, but I won’t assume anything since I don’t think it’s my place to say.

Heroic Bloodshed is a sub-genre often attributed to John Woo, with A Better Tomorrow generally regarded as the first true example of such, and as true as that might be, The New One Armed Swordsman certainly serves as a precursor, particularly with its central relationship.

Lei Li is a deeply sad character, holding deep regrets for the choices he made that led to his defeat and drifting through life, allowing whatever pain to come his way because humiliation is something he feels he deserves; when Fung comes along, he sees the strength that lies within him that he’s buried beneath all the pain and attempts to bring it out of him.

Their first real conversation, after Lei Li has been humiliated by local bullies after attempting to defend Ba Jiao, only for Fung to step in, has all the hallmarks of a Meet Cute; their hands brush as Fung hands Lei Li a towel and almost immediately, he seems to have him figured out — “People say real fighters don’t show their strength.”

This quote, whilst quite literal in the context of the movie, can be read multiple ways, but in a queer perspective, it’s quite relatable — Fung is feeling the situation out, sensing Lei Li perhaps is different like him, though is attracted by his choice to not live a life of a swordsman, something he too longs for.

Queer people also relate to the idea of hiding something about themselves, perhaps due to shame or trauma, and so Lei Li’s predicament also seems fairly familiar, if not taken literally.

Over their next few scenes, as Lei Li continues to struggle with the weight of his past (Ba Jiao attempts to cheer him up by bringing him a sword, but this only triggers his terrible memories of the day he cut off his arm), Fung seems to become even more bowled over by him, curious about his reasoning for leaving such a life behind; it’s when he finds out Lei Li’s true identity that it seems to click for him.

After an attempted kidnapping of Ba Jiao, the two men finally start to connect, and display more physical affection than a number of actual romantic couples from this era of Shaw Brothers, especially from Chang Cheh — whilst occasionally his films would feature kissing (Dead End and Vengeance! go the furthest with implied love scenes), generally PDA in his films is chaste, most of the time just being hugs that last a few moments.

Lei Li and Fung, however, can’t seem to keep their hands off each other — they’re constantly touching in the three or so scenes that fill this pre-climax, putting an arm around each other’s shoulders, squeezing arms. When they aren’t touching, they are gazing at each other (as Ba Jiao stands rather awkwardly to the side) and declaring how happy they make each other, planning to retire together to become farmers. Fung remarks jokingly that Ba Jiao won’t be interested in joining them, and the scene plays like they’re planning to elope.

Elements of the two leads’ relationships also feel somewhat reminiscent of the later burgeoning buddy cop genre, though admittedly lacking the initial adversity that would class it as such — Chiang and Ti’s films where they would be allied up often incorporated some of these tropes, putting them as potential precursors to one of my favourite genres.

Though it probably begets it’s own article so I won’t dwell on it too much, homoeroticism in the buddy cop genre is almost a trope in of itself. Often, the pairings are same sex, and though they may butt heads, they end up providing a key element the other is missing.

With Riggs and Murtagh from Lethal Weapon, they provide a reason to keep going, a family; with Kenner and Murata in Showdown in Little Tokyo, they provide each other a culture clash, learning and successfully avenging Kenner’s family.

Here, Ti and Chiang similarly provide each other something; Lei Li is deeply traumatised and haunted from losing both his arm and his confidence, and Fung is the only one who seems to be able to make him not hate himself, if only fleetingly. Likewise, Fung is clearly a little tired of being a fighter and seeks a simpler life; he admires Lei Li’s ability to step away and yearns to do the same.

What starts as respect blossoms very quickly into genuine connection and adoration, which makes it ever the more effective when the film takes a tragic turn.

If you’re familiar with the works of Chang, you’ll be aware of his tendency to kill off characters in the most garishly violent of ways — men will fight to the death with their guts hanging out, eyes gouged and quite literally spraying blood. He’s never one to shy away from a masochistic look at the male body, whereas women typically are dispatched of quickly and without fanfare in a sort of inverse of the American slasher genre that would follow the following decade.

Fung’s death here is one of the most horrific sequences Chang’s ever crafted — quite literally, he is cut in half, after being hauled up in the air by ropes like a marionette puppet. Though the moment itself is brief (we see a quick shot of the two halves separating and Fung screaming before he dies), it’s surprisingly effective, as is the aforementioned moment in which Lei Li swears revenge, which features probably my favourite piece of acting from Chiang — it’s remarkably subtle, but you can really feel the bubbling rage and grief in him as he makes his decision, knowing it might cost him his life.

The final act of this film is one that has a surprisingly emotional undercurrent, much more than usual for a Chang Cheh film — there’s a moment where Lei Li finds Fung’s crudely crafted grave outside the temple where he was murdered and seems to be on the verge of tears as henchmen surround him which is particularly potent.

Easily the most striking moment, however, is when he faces up against Ku Feng’s villain, declaring that he is here to accompany Fung in death after the villain taunts him. It’s a suitably profound moment, really showcasing the effect the man had on him, despite only knowing him for a few days at the most.

In the end, Lei Li defeats the villain, but the ending feels more than a little bittersweet, even as he reunites with Ba Jiao — they embrace on the bridge, dead bodies littered around them and still, Lei Li can’t help but look a little sad.

To conclude, The New One Armed Swordsman is, at least in my opinion, Chang Cheh’s strongest film, and one that deserves much more appreciation in his oeuvre.

With its strong performances, focus on character and dynamics over mindless action and yes, undercurrents of queer romance, it’s one of his most compellingly written works, with Ni Kuang delivering a script that is surprisingly tender and sweet at moments, but also manages to pack a strong punch with it’s finale.

It serves as a great precursor to the Heroic Bloodshed genre with its themes of male bonding and masculinity and features perhaps the strongest pairing of Chiang and Ti characters.

Definitely check this one out, as it deserves the love and attention. The next article I’m going to be working on is a eulogy for the failed experiment that was the DCEU. Don’t forget to follow my twitter, and if you like this film, feel free to comment or whatever.